Tom Robbins passed away on my last birthday. I had begun reading his reviews when he worked for a great metropolitan newspaper and eventually read almost all of his novels and essays. It has been surprising to learn that many of my friends knew him personally though I never did.

Tom Robbins passed away on my last birthday. I had begun reading his reviews when he worked for a great metropolitan newspaper and eventually read almost all of his novels and essays. It has been surprising to learn that many of my friends knew him personally though I never did.

His writing and being had great influence on my thinking – for the better. To start, school assignments seemed to always be short term things where the assignment was given one day and due only a few days later. Never very good at quick work, I have always preferred essentially carving a drawing into existence in a slow process. Robbins offered the alternative I needed.

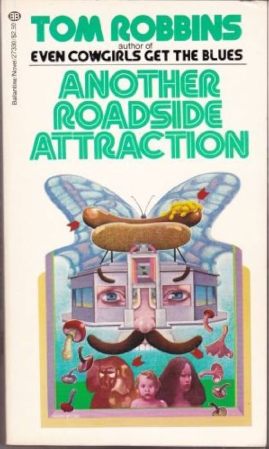

On a return trip from Canada through the vast openness of Montana (were we smuggling stuff?) I found a paperback copy of ANOTHER ROADSIDE ATTRACTION. Then, staying outside Missoula at a lovely place with a pool, we sat around the pool and took turns reading from Robbins’ book. We laughed until management told us to cool it then packed off to sleep. I, though, continued reading. Somewhere in the next few days I found this paragraph:

The magician was at work on his magical things. Sprawled upon a pallet of skins, he attended to his maps, charting a course with feathers and inks and wooden calipers. Unlike poor Rand McNally, Ziller was not obliged to limit his cartograms to representations of the earth’s familiar surface; no, his maps could and did indulge in languorous luxuriation, in psycho-cosmic ornament that may or may not be helpful to motorists seeking the most convenient route from there to here.**

The opening sentence captivated me as “the magician was at work on his magical things” was the antithesis of what I’d been told should be true about drawing. For a magician, a drawing need not be made and finished at the same time as it should be like charting a coastline or other edge of unknown space — not to be done in haste. I have been forever indebted to Tom Robbins for that insight…. As one enters a professional sphere of working, sometimes really juicy insights hit hard and when the light comes on [Roshi], it stays on.

The opening sentence captivated me as “the magician was at work on his magical things” was the antithesis of what I’d been told should be true about drawing. For a magician, a drawing need not be made and finished at the same time as it should be like charting a coastline or other edge of unknown space — not to be done in haste. I have been forever indebted to Tom Robbins for that insight…. As one enters a professional sphere of working, sometimes really juicy insights hit hard and when the light comes on [Roshi], it stays on.

Those familiar with my work may also note similarity with what Robbins’ describes:

If, with appropriate geographical symbols, they indicated the presence of mountain ranges, forests and bodies of water, they seemed also to indicate psychological nuances, regional flavors, genito-urinary reactions and extrasensory phenomena—those “other dimensions” of voyage so well known to the aware traveler. His charts had the look of embellished musical compositions. Perhaps they were. (The London Philharmonic Orchestra will now perform Map of the Lower Congo by John Paul Ziller; scale, three-quarters of an inch to the mile.) **

The pursuit of magic followed along as I began fabricating books. It was vividly clear that books should be influential leading me to believe a home-made cartographic symbol base could be a design foundation for the actions seen in the book. After all, this foundation could help binding, surface design and interior content begin to achieve that wonderful phrase “one with everything.” This is, of course, an ideal while we make within the physical world where work must always lack perfect symmetry of form and idea. What we like to consider “art” exists only in the ideal world to become, in the physical space, not art but paintings and sculpture and architecture with leaky roofs — all manner of things always begging for refinement. (Art of course is also a catch term for art categories or a study of the ideas and history but anyone calling a work “art” is referring to something which exists only as mindspace.)

The pursuit of magic followed along as I began fabricating books. It was vividly clear that books should be influential leading me to believe a home-made cartographic symbol base could be a design foundation for the actions seen in the book. After all, this foundation could help binding, surface design and interior content begin to achieve that wonderful phrase “one with everything.” This is, of course, an ideal while we make within the physical world where work must always lack perfect symmetry of form and idea. What we like to consider “art” exists only in the ideal world to become, in the physical space, not art but paintings and sculpture and architecture with leaky roofs — all manner of things always begging for refinement. (Art of course is also a catch term for art categories or a study of the ideas and history but anyone calling a work “art” is referring to something which exists only as mindspace.)

In the early 1980’s, I began teaching at The Oregon School of Arts and Crafts (R.I.P.) whose name was later changed to a college instead of a school (for some arcane reason). At this wonderful school, I made new, treasured friends and met makers from disciplines completely novel to me. The textile arts introduced me to “piecing” right when I was also learning about leather mosaics on bindings. These ideas of small parts contributing to a firm gestalt was exciting so I began to make small parts for bindings and small modular templates to serialize certain passages.

In the early 1980’s, I began teaching at The Oregon School of Arts and Crafts (R.I.P.) whose name was later changed to a college instead of a school (for some arcane reason). At this wonderful school, I made new, treasured friends and met makers from disciplines completely novel to me. The textile arts introduced me to “piecing” right when I was also learning about leather mosaics on bindings. These ideas of small parts contributing to a firm gestalt was exciting so I began to make small parts for bindings and small modular templates to serialize certain passages.

It might seem relying on small parts is a common operational method used by many artists. In my case, when these few dots connected, a wiggly kind of enlightened blow occurred. It was a very potent thing similar to when I first had fresh rosemary while in Venice.

From this, three favorite assembly concepts developed with piecing, tiling and Tessellations. There are others of course but we will focus on these as brevity is sometimes blessed.

Piecing:

In 1981 I was visiting a friend in Japan. Her research was into (I think) a piecing niche in the history of textiles. To quote her,’ The Buddha wore rags’ and this idea took her on a fantastic labyrinthine ride into the history of the robes of Buddhist priests. Such robes were pieced together from cast off Kimonos to become technically rags — but elegant ones. There was also a formality where, like tatami mats (if I remember correctly), the rectangles were either root two rectangles or very close to a golden rectangle. (Must check my notes.) The overall size of the of the robe echoed the scale up of the rectangle and this was worn over the left shoulder. I have no idea how widely this design radiated into the world but every time I see a photo of the Dalia Lama, I am reminded of such pieced adventures. Can’t tell if his robe follows this same design or if it came to Japan from some other source.

In 1981 I was visiting a friend in Japan. Her research was into (I think) a piecing niche in the history of textiles. To quote her,’ The Buddha wore rags’ and this idea took her on a fantastic labyrinthine ride into the history of the robes of Buddhist priests. Such robes were pieced together from cast off Kimonos to become technically rags — but elegant ones. There was also a formality where, like tatami mats (if I remember correctly), the rectangles were either root two rectangles or very close to a golden rectangle. (Must check my notes.) The overall size of the of the robe echoed the scale up of the rectangle and this was worn over the left shoulder. I have no idea how widely this design radiated into the world but every time I see a photo of the Dalia Lama, I am reminded of such pieced adventures. Can’t tell if his robe follows this same design or if it came to Japan from some other source.

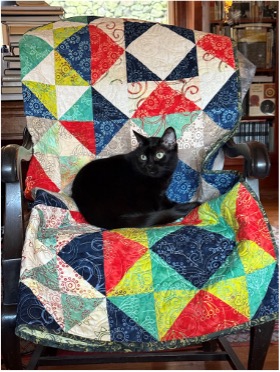

But as with many things in my process, what I was already doing came to have a name. When I met my wife she introduced me to all manner of other overlooked fabric ideas as her family boasts several quilters (including herself) of great skill. Piecing is a dynamic way to assemble and carries within it a nested set of killer moves with which to beguile the eye.

But as with many things in my process, what I was already doing came to have a name. When I met my wife she introduced me to all manner of other overlooked fabric ideas as her family boasts several quilters (including herself) of great skill. Piecing is a dynamic way to assemble and carries within it a nested set of killer moves with which to beguile the eye.

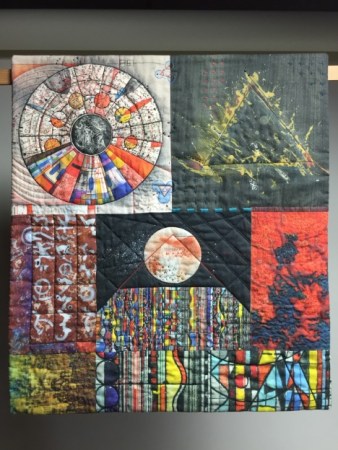

My wife, Ann, and I have collaborated on various projects. Here is a quilt she made from my drawings which was then transferred to fabric and sewn once more.

Tiling:

When the first Star Wars movie was released, all of us hardware nuts were impressed with the surfaces of these monstrous star ships as everything was seemingly wrapped in a kind of cosmic plumbing. Filmed from physical models, I learned that existing model kit pieces were used to make a flat surface look highly figured with hatches, gun turrets and mostly unknown functional equipment seemingly necessary for the conquest of the universe (as seen in the Millennium Falcon model in the attached image). This dazzling idea led movie spaceships and the like to change.

Later, mid 80’s the Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C., a part of the Smithsonian, had an exhibition featuring Star Trek. It centered around the first TV series and the two or three movies made up until then. I recall the little chips that Spock would insert into his computer console and was amused to see that they were just bits of poorly painted wood. Over the TV, they were very technically advanced.

Later, mid 80’s the Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C., a part of the Smithsonian, had an exhibition featuring Star Trek. It centered around the first TV series and the two or three movies made up until then. I recall the little chips that Spock would insert into his computer console and was amused to see that they were just bits of poorly painted wood. Over the TV, they were very technically advanced.

The total killer came from ‘’The Undiscovered Country’ in the form of a Klingon Bird of Prey. It was easy to see some form had provided the contours of the ship [wood or foams] but it was covered in small tiles which I speculate [and am pretty certain] were hundreds of small photo etched bits of metal. All over it was painted in that light leisure suit blue so I couldn’t see what the metal was. But the effect of closing in on THAT beautiful mechanical and utterly alien surface design really moved me. This sighting bumped my metal work and jewelry into a new direction. No image is included to show this but in the early part of the movie a close up takes place and, if you are ready for it, the surface richness is revealed.

The total killer came from ‘’The Undiscovered Country’ in the form of a Klingon Bird of Prey. It was easy to see some form had provided the contours of the ship [wood or foams] but it was covered in small tiles which I speculate [and am pretty certain] were hundreds of small photo etched bits of metal. All over it was painted in that light leisure suit blue so I couldn’t see what the metal was. But the effect of closing in on THAT beautiful mechanical and utterly alien surface design really moved me. This sighting bumped my metal work and jewelry into a new direction. No image is included to show this but in the early part of the movie a close up takes place and, if you are ready for it, the surface richness is revealed.

Tessellations:

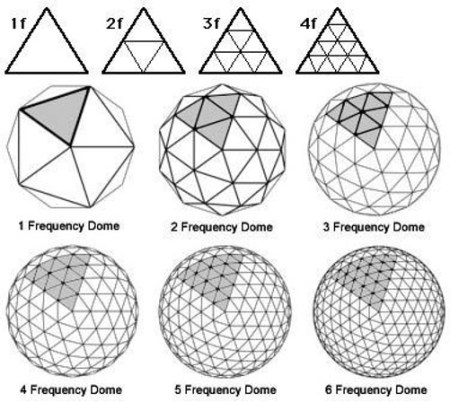

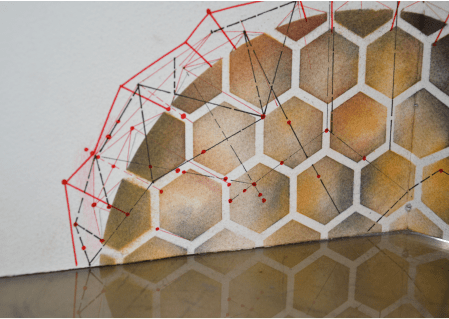

Tiling and Tessellations are a branch of mathematics that interest me as a visual artist. I like how certain Tessellations, usually regular can be folded into planar shapes. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion map first seen in Life Magazine, March 1943, is a world map fitted to realistic scale into the triangles of an icosahedron. This world is so very different from our habitual Mercator distortion but even today I have to put in some effort to deal with Fullers despite it being far more accurate with landmasses reflecting their actual size. Yet it turns out temperature zones set the patterns for history and the mind tends to wrestle with cultural habits….

Tiling and Tessellations are a branch of mathematics that interest me as a visual artist. I like how certain Tessellations, usually regular can be folded into planar shapes. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion map first seen in Life Magazine, March 1943, is a world map fitted to realistic scale into the triangles of an icosahedron. This world is so very different from our habitual Mercator distortion but even today I have to put in some effort to deal with Fullers despite it being far more accurate with landmasses reflecting their actual size. Yet it turns out temperature zones set the patterns for history and the mind tends to wrestle with cultural habits….

I love to draw Tessellations using 3, 5 or 8 sided forms and always learn a little something new as I work inside of these borders. The dynamics of Fuller’s domes continue to dazzle me and I am still not fully confident in drawing those complex little wonders……lines, math and bending things precisely is a challenging task.

I love to draw Tessellations using 3, 5 or 8 sided forms and always learn a little something new as I work inside of these borders. The dynamics of Fuller’s domes continue to dazzle me and I am still not fully confident in drawing those complex little wonders……lines, math and bending things precisely is a challenging task.

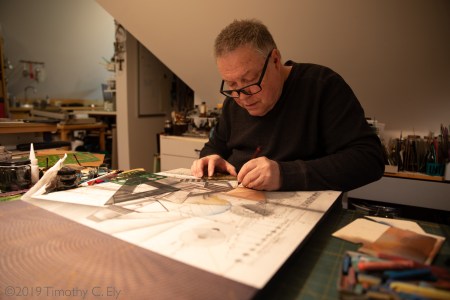

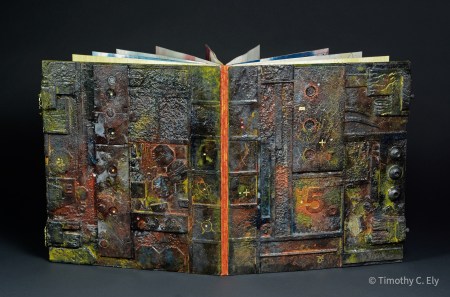

Returning to structural piecing, I am currently at work on a book titled MUSE with a floating joint at the spine and the board fixed in place by the webbed sewing supports. These supports are laced under and then brought out to the top of the board and resolved.  The boards themselves are made from a large number of small pieces of board laminated together and finally pegged with hardwood dowels. These dowels are strategically placed to amplify the rigid qualities of the board fabrication method. The top layers are treated with carving and stamping and edge coloring resulting at times in a multi-D experience. A friend says I am building a starship with the text of the book the operations manual!

The boards themselves are made from a large number of small pieces of board laminated together and finally pegged with hardwood dowels. These dowels are strategically placed to amplify the rigid qualities of the board fabrication method. The top layers are treated with carving and stamping and edge coloring resulting at times in a multi-D experience. A friend says I am building a starship with the text of the book the operations manual!

With all of this I turn back to Tom Robbins. His reference to Ziller at work on his maps of the Congo was a fantastic place to pivot and to awaken to the idea that work need not be finished in clock time but in a more realistic time such as provided by the beating of a heart. As with all things, it seems that it showed up for me at precisely the right moment.

Until next time, best for all.

Until next time, best for all.

T.

©2024 — Timothy C. Ely — All Rights Reserved

**Another Roadside Attraction, Tom Robbins, 1971, p 105 of 404 in KOBO epub

Pingback: Hot, Then Smoky | Byopia Press

I owe you an inspirational credit. I was deep in the stacks of reference books on fine bindings, working on my set book at North Bennet Street School, and feeling “…constrained by too many rules or concerns.”, when I found your 2023 article, The Only Constant, in The New Bookbinder.

My decades of experience using fiber and paper scraps; piecing to create patterns, and layers of meaning seemed culturally and artistically distant from the images of pristine leather and gold tooling I was seeing on volume after volume. Reading your article then, and this one now, I found/find myself saying “Yes, … YES!” Reading your article then helped me navigate my own way through the constraints of the set book project. Reading this one now, gives me a map pin, firmly pushed in marking my starting place, as I map my continuing adventures.

Thank you so much for sharing your thinking and work.

Sandra Haynes

LikeLike